Various long-form thoughts that are too small, vague, circumstantial, incomplete, or nonlinear for an essay.

I tried to write this one in a more thorough style than the previous linkpost, but found it tedious, so it has a lot fewer links. Probably I'll do the next one somewhere in between, and build it over the course of the month.

Lifespan of neurons is uncoupled from organismal lifespanThe Anthropic Landscape of String TheoryShapley values: Better than counterfactualsFive Mistakes in Moral Mathematics, by Derek Parfit, linked by above; every philosopher should be forced to read this at gunpointShapley Values II: Shapley Strikes BackLiving Out the Past: Infant Surgery Prior to 1987, on the long-term trauma caused by undergoing surgery w/o anesthesia due to consciousness "science"Multivacuum initial conditions and the arrow of time, on inter-vacua tunnelling constants and relative production rates of Boltzmann brainsConsciousness as a conflationary alliance term for intrinsically valued internal experiencesCultivated Meat: A Wakeup Call for OptimistsStatistical Structure of Quantum Theory, clear exposition of quantum mechanics as a theory of information rather than physicsComputational Capacity of the Universe, by Seth Lloyd. Calculates that "The universe can have performed no more than $10^{120}$ ops on $10^{90}$ bits". Apparently $10^{120}$ comes about as $ N_{ops} = \frac{t c}{G \hbar}$, where $t$ is the age of our universe, and $10^{90}$ as $N_{bits} = N_{ops}^{3/4}$.Does a Rock Implement Every Finite State Automaton, David Chalmers. Use the CSS style body {margin-left: 12.5%;margin-right: 12.5%;margin-top: 2em;margin-bottom: 2em;font-family: sans-serif;line-height: 1.25em;background-color: #fcfcfc;color: #181818;} h2 {text-align: center;font-size: 2em;} h3 {font-size: 1.5em;padding-top: 1em;} to make his site legible.1. On the incomprehensible vastness of the multiverse.

(Radioactive Decay) Chances are, you've been near an ionization smoke detector recently. These devices have a curious method of operation: if you were to take one and open it up, you'd find two chambers of air inside, one sealed, one not. Both are ionized to the same degree, which allows them to drive equivalent currents; when smoke enters the open chamber, it binds to the ions there, causing a detectable decrease in current -- this triggers the alarm. Because the chamber is open, though, it needs a stable source of ionizing radiation within to continuously replace the ions that leak out.

To solve this problem, such smoke detectors typically contain a 0.29 microgram pinprick of americium-241, an anthropogenic element that produces lots of highly ionizing yet harmless alpha particles. This corresponds to: $$\frac{0.29 \times 10^{-6}\ \text{g}}{241 \ \text{g} \cdot \text{mol}^{-1}} \times \left(6.022\times 10^{23}\ \frac{\text{atoms}}{\text{mol}}\right) = 7.23 \times 10^{14} \ \text{atoms}$$ 723 trillion atoms. Since each has a half-life of 433 years, approximately 37,000 of them decay each second into neptunium-237, which, with a 2 million year half-life, is basically static in comparison to americium-241.

(Chaos Theory) The design of a smoke detector guarantees that these alpha particles will go on to strike air molecules in a region contiguous with the open air [^inwards]. Each collision alters the trajectory of a single molecule; let's suppose the influence of the particle is limited to this collision. Since air molecules are constantly pinballing off of one another at around 500 m/s, with a mean free time between collisions of 0.2 ns, this alteration quickly cascades, with the initial air molecule that is now moving in a different direction than it would have had the alpha particle never existed going on to strike more air molecules in different ways, which then strike even more air molecules, and so on. The end result is essentially a shockwave, traveling outwards at a speed much greater than 500 m/s (it is the molecules on the extreme right tail of the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution that reach distant areas first), within which the "random seed" has been changed by the specific time and direction of the alpha decay event. The air molecules within this expanding shockwave have all had their micro-scale trajectories randomized by the chaotic effects of that one event.

Macro-scale phenomena are left unaltered—a fan will blow the same amount of air at the same velocity, but the specific molecules it blows, and their specific positions and trajectories will be entirely different. Nor will the temperature of the air have appreciably changed, (save through the energy added by the alpha particle), but the random trajectories of molecules instantiating that temperature will have been totally shuffled

(Butterfly Effects) Consider a single UV-B photon, traveling through the atmosphere in your direction. The primary determinant of whether it hits you is whether or not it gets absorbed by an air molecule in its path. As the vast majority of air is empty space, the photon is usually unimpeded, so, like a squirrel scampering across the freeway, it just has to get "lucky" enough not to get hit by an interceding air molecule before it reaches you. Because of this, every microstate-scrambling shockwave will randomize which particular photons get absorbed, and, consequently, the points where you get hit. But the effect of individual UV-B photons is not the sort of thing that, like wind speed or temperature, is smoothed out by the law of large numbers: if a UV-B photon reaches you, it hits one molecule in one cell, and that reaction can spiral out of control, ultimately producing one more mutation

A melanoma, for instance, may have only developed because an alpha decay occurred at the exact nanosecond that it did, causing the chain reaction of chaotic air molecule collisions that it did. If this alpha particle had not been emitted in one particular direction during one particular nanosecond of one particular day, your life could have been completely different.

(Decoherence) Each of these decay events is quantum indeterministic: it happens at a random time, sending an alpha particle in a random direction. As the exact effects of the initial decay interact with the wider environment in ways that leave macroscopic records, the initial superposition of possible decay data decoheres into a mixture of classical states, creating a new distinct "branch"

What there is is decoherence, which causes the wavefunction to rapidly split into a weighted (not uniform) mixture of effectively (not ontologically) distinct components, as the records of a specific quantum-indeterministic effect spread outwards, becoming entangled enough with their environment that components of the mixture corresponding to different superposed states become effectively (not ontologically) independent and incapable of interaction. This is the process that creates the appearance of wavefunction "collapse" (according to Born rule probabilities) within a quantum state that evolves solely according to the Schrödinger equation. No artificial notion of ontological collapse has to be appended to standard quantum mechanics in order to get the world we see.

Fix 38,000 decays, and ignore direction. From 723 trillion atoms, the variety of ways that 38,000 atoms can be chosen is:

$$\binom{7.23e14}{3.8e4} = \frac{7.23e14!}{(7.23e14-3.8e4)!(3.8e4!)}$$ $$\approx \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \frac{\sqrt{7.23e14}}{\sqrt{7.23e14-3.8e4}\sqrt{3.8e4}} \left(\frac{7.23e14}{e}\right)^{7.23e14}\left(\frac{7.23e14-3.8e4}{e}\right)^{-(7.23e14-3.8e4)}\left(\frac{3.8e4}{e}\right)^{-3.8e4}$$ $$\approx 10^{407116}$$

This is for exactly 38,000 decays (disregarding all the branches with 37,999 etc.)

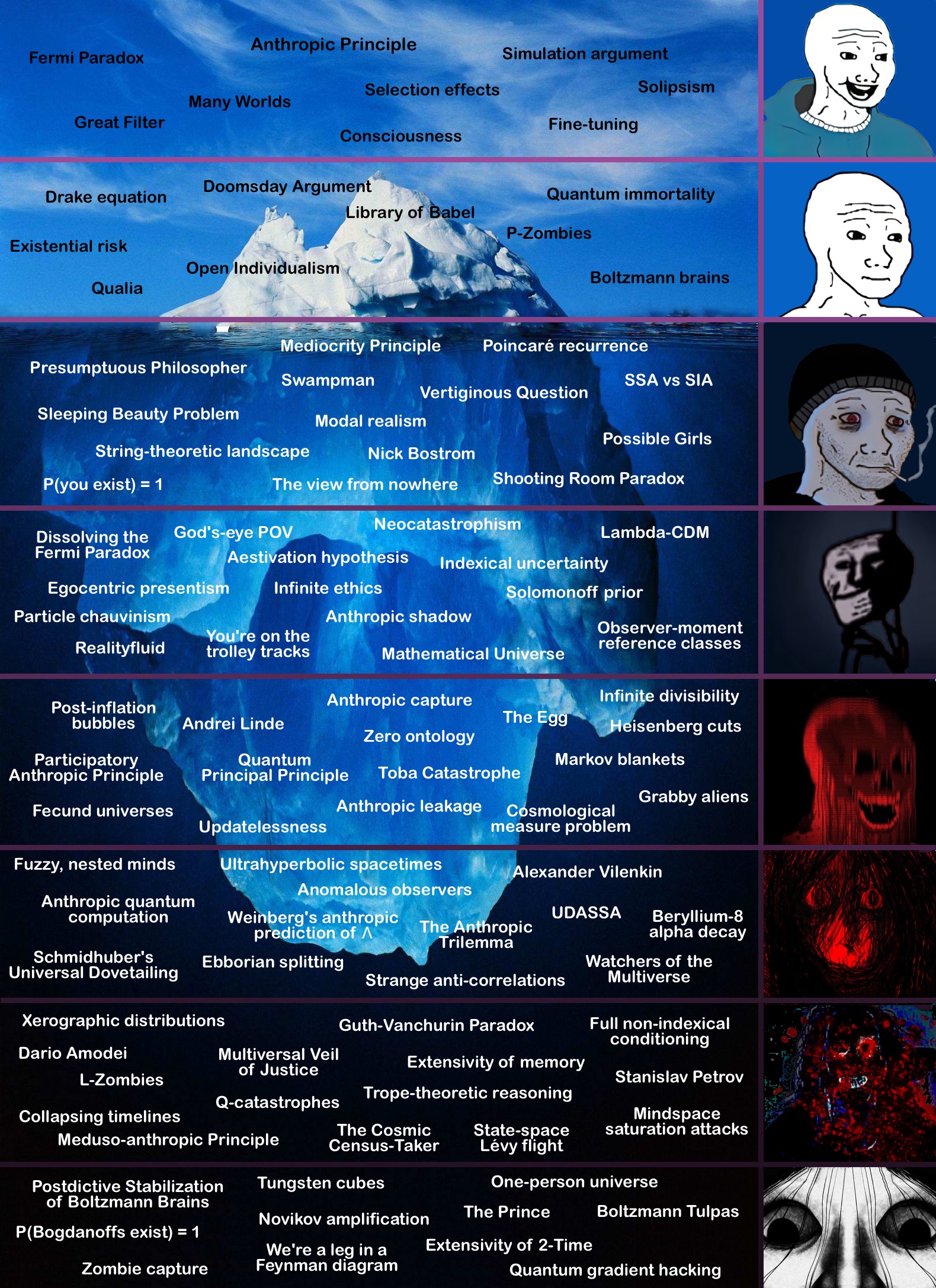

An iceberg chart I made on the subject of anthropics (original post):

Explanations

Partial explanations for some of the lower topics, particularly ones that aren't really google-able. More entries may be added in the future.

In comparison to Tegmark levels 3 (the many-worlds interpretation) and 4 (the mathematical universe hypothesis), levels 1 and 2 are discussed far too rarely. They're entirely non-metaphysical ways in which a single history of a single reality, like this one, may end up being a multiverse unto itself.

Level 1 is only the deduction that, if our universe is spatially unbounded (which seems likely, given its large-scale homogeneity and near-flatness), then there are infinitely many Hubble volumes; since there are only finitely many states each one can take (b/c quantum), and each one is possible (b/c quantum), each state must occur infinitely many times. In the ensemble of all copies of any given state, such as...this ...state (it's gone now), even Copenhagen-style quantum randomness will cause different copies to evolve in different ways according to the Born probabilities, which roughly 'simulates' an MWI multiverse by repeated sampling of the wavefunction within a single universe.

Level 2 has to do with an unsettling quirk of our models of cosmological inflation: they generally don't want to end. Basically, we model inflation as driven by the potential energy of a field in a false vacuum state; there'll occasionally be points at which the field quantum-tunnels to the true vacuum, and these vacuum decay events will ~irreversibly form bubbles inside of which inflation has ended. Our entire (inflation-free) universe is, in such models, one such bubble of spacetime, embedded in a "big spacetime" that's still inflating. Being true vacuums, these bubbles will continue to grow in number and size, but the rate of inflation outside the bubbles is so much faster than their own growth rate that they'll never completely take over the big space. There's a sort of cosmological thalassophobia that comes along with the idea that there is an edge to space as we know it, and, beyond that, an entirely different sort of space of incomprehensible size—compared to our entire universe!—and energy.

If there's a multiverse, and we're presently in a false vacuum state, then, since some proportion of the infinitely many copies of our world is always being destroyed by indeterministic vacuum decay events, we're constantly leaking anthropic measure. This is a discount rate on all future utility: nothing matters to you if nothing exists, and your whole world constantly dwindling in existence

Yet, what if it were, say, 80% lost per second? How could we tell? Since vacuum decay bubbles expand at c and kill us instantly, we can't ever observe them. As a hypothesis, this'd be unfalsifiable, with no observable effects - but its truth would matter more than anything else! Aside from strategies with payoffs at future times $T$ asymptotically greater than $5^T$ utils, the best way to maximize expected utility in such a world would always be greedy, Bacchanalian utilization: total, rapid consumption of all your resources.

But here's the especially scary thing about a world where this is true and we don't know it: consider how artificial superintelligences would act. If they can deduce this from available data, or a priori, then, having done so, they'd instantly go berserk from our perspective! For instance, say you give an android body to an ASI and tell it to maximize your net worth. You turn it on, and, after thinking for a few seconds and fetching some cosmological data, it suddenly sprints towards the couch, furiously looking for lost pennies to throw at you! Of course, our anthropic leak rate is almost certainly nowhere near 80%/sec. But this is a proof of concept that:

I find this phenomenon very interesting, and terrifying, from the perspective of Knightian uncertainty. The very fact that there can be this sort of additional multiplicative factor on value, and that it's only revealed to us by way of advances in our cosmological knowledge, raises the question of what else there might be about the ontological-shape-of-reality that we don't know and really need to know!

Note that on expected value, this argument goes through even in a single Copenhagen universe in a false vacuum state. The multiverse only converts this expectation with a certain probability into actuality at a certain proportion. It has happened, is happening, and will continue to happen. Specifically, this goes through in actuality for Tegmark 1, 3, and most 2-style multiverses

Type 1 (other Hubble volumes): 0.6

Type 2 (other bubble universes): 0.7

Type 3 (MWI): 0.75

Some other manner of infinitely-divisible multiversity (e.g. as might arise from MUH or another form of modal realism): 0.5

I suspect these are more or less independent, save for certain really strange scenarios in which they commonly fail, as well as other technical forms of dependence whose effect I can't really gauge, so my p(multiverse) = 1 - 0.4 * 0.3 * 0.25 * 0.5 = 98.5% - x-factor > 90%.

False vacuum (aka metastability of the Higgs field) is far less certain imo, perhaps 75%. It strongly depends on what physics lies beyond the standard model, but I think that the fact that the SM seems to predict metastability should anchor our priors on what future theories that explain our reality will predict.

Note: See also this LessWrong post by Stuart Armstrong, which I found (after writing the above) makes many of the same exact points in the same exact way...

One underappreciated feature of the many-worlds multiverse: since our present night sky is the result of microscopic quantum fluctuations shortly after the big bang being expanded to cosmological scales by inflation, the multiverse contains every possible night sky.

In fact, insofar as the rise of human civilization has some statistical independence from the specific arrangement of matter in our universe, [note] the multiverse is going to contain human civilizations under all sorts of night skies. And, save for the effects of our planet's being in a forearm of some mid-sized spiral galaxy at around T+14 billion years, I think it more or less is independent outside of a few exceptional timelines (assuming this isn't one, which I think is anthropically permissible?).

Most of these human civilizations probably look up to the same sort of belt that we do (pictured), but with random orientations, positions, and sizes. The vast majority of the structures internal to the belt, and nearly everything outside the belt, will also be randomized. Incidentally, this might serve as a refutation of some forms of astrology: the stars are, to us, random, so if constellations have any predictive power within our civilization, it's either through direct physical effects or mere statistical correlations, rather than non-physical forms of causation.

Note: There are obviously going to have been situations in our timeline's history where e.g. a cosmic ray from the Andromeda galaxy sterilized some proto-corvid whose genes could've otherwise led to a civilization of superintelligent crows, or some prehistoric simians accidentally scared away a pack of lions by freaking out upon seeing an extragalactic supernova (like SN1987a), or (far, far more likely!) much longer, weaker, and more chaotic chains of events happened through which our specific night sky somehow determined the existence of our civilization.

But all such scenarios are going to be either directly quantum-indeterministic, or they'll act upon what is already a massive ensemble of subtly different worlds, leading to subtly different effects to be massively expanded by chaos. There will be other timelines where our specific night sky therefore has no humans to see it; each distribution of matter can only be said to have a propensity with which it generates human civilization. Hence "statistical independence", or relative invariance of propensities across different matter distributions. We can assume for anthropic reasons that ours is somehow special for unknown complicated (randomly constructed, and almost certainly NP-hard to formally compute due to mutual dependencies) reasons, but it's likely not that special.

Theologically speaking, can sufficiently well-developed tulpas and alters in a single brain go to different afterlives? I think split-brain cases are a proof of concept for a 'unit of judgement' below individual organisms, but how fine can we get? can we split based on, say, IFS? A metaphysical algorithm for judging souls should, in theory, work on all possible configurations of soul-housing systems like minds, no matter how exotic. I feel like this severely penalizes the standard {heaven, hell} dichotomy, to the point that it starts to break down in coherence if we consider sufficiently complicated real-world situations.

Some baseless speculation: Say we put the brains of Ted Bundy and Mother Teresa into two neighboring vats, feeding them each a made-up stream of perceptual data so they think they're still living their everyday lives in their ordinary meat bodies. These are clearly two individual souls, which we assume are going to separate afterlives. Now, perform hemispherectomies on both, leaving Bundy-Left and Teresa-Right. As an operation, hemispherectomy actually has far fewer complications than you'd think, to the extent that B-L and T-R would continue to think, act, and identify in the same ways as B and T; still two souls, separate afterlives. But what if we put B-L and T-R in a single vat, side-by-side, synced up their perceptual streams (say by anesthetizing both), and then started reconstructing a corpus callosum, neuron by neuron, to connect them? While it's clear that we're going to hell for doing this, to which afterlife does the resultant meeting of the minds go? Or, more interestingly, what determines whether it goes to one afterlife or two?; at what point in the continuous brain-merge does the discrete soul-merge happen?

Interestingly, this line of thinking gives us a way to experimentally test certain claims of interactions with the deceased by using Schrödinger-like setups to propagate superpositions to afterlives: asssuming WLOG that the merged brain goes to heaven, say we put B-L, T-L, and T-R in a vat in a sealed catbox containing a machine that measures a qubit to decide which left side to connect T-R to, and then atomized everything inside so as to instantiate afterlife assignments. To an observer outside the sealed vat, hell itself would now have to be in a superposition of having and not having Ted Bundy; if there were any causal influence of his being in hell on the state of an observer in the world (e.g. haunting, possession, other demonic phenomena, scrying mechanisms), this would cause the vat's state to decohere, which is experimentally measurable. The same goes for the presence or absence of a 'pure' Mother Teresa in heaven, such that e.g. saintly miracles contingent on said purity would also cause a verifiable loss of coherence. So Catholicism might be experimentally testable in principle...

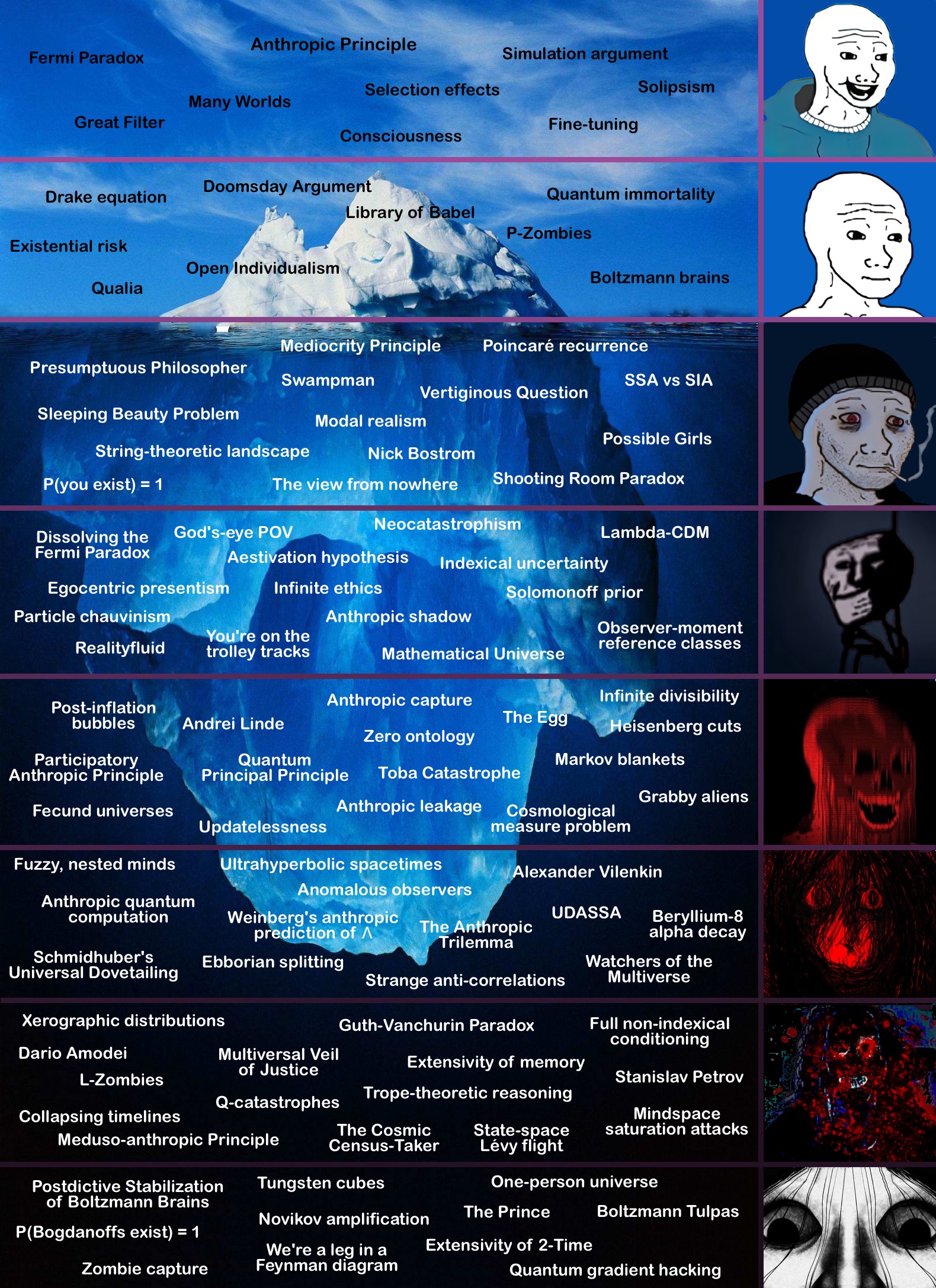

I'd like to see text-based simulation games that simulate what the lives of wild animals are actually like. They'd likely have to be deep mechanically and disturbing experience-wise. A quick example sketch:

Would also help delegitimize the myth of wilderness as idyllic. Only so many times you can read

before realizing that something's really, really wrong

Notes

Why is it that, despite the fact that a dog can only be a dog by sole virtue of the particles comprising it, you can know with near-certainty from its external appearance that it will behave "like a dog", panting and barking and licking and biting and doing other things that aren't legible in the slightest from the perspective of the most fundamental physics we know? These phenomena all supervene on the mechanistic behavior of octillions of particles that do not a priori admit any such notions; the fact that such microstate dynamics are sufficient to characterize the entirety of physical reality seems to leave no room for the objective existence of things like "dogs", which we're forced to understand as mere pointers to clusters of particles. The implicit conclusion we often take away from our knowledge of fundamental physics, I think mistakenly, is that such physics is the sole truth of what's real and what exists, such that all knowledge about reality is only knowledge insofar as it can be reduced to scattering amplitudes and wavefunctions.

But all science, with the tentative exception of some esoteric fields of 20th century physics, has hitherto proceeded, and will continue to proceed, on the basis of such "convenient fictions". Where in the Standard Model is Darwinian evolution, or scurvy? Why can we reason about these fictions as though they had causal power in themselves without first reducing them to matters of particle physics? For that matter, consider the dog. The particles that make up a given dog constantly swap themselves out over the course of months as it consumes food and excretes waste, but the dog itself remains, and continues to bear the same causal powers (e.g., barks at passing cars, sheds fur everywhere) regardless of these particles.

This is the transcendental condition for the possibility of science: that reality admits structures across a continuum of levels of abstraction, with levels below determining those above, and with structures at a given level acting through the causal powers attributable to them at that level to condition other structures at that level. Medical science is possible because human bodily failures tend to be legible to the high-level semantics of human physiology that makes sense of things like a "nervous system", "respiration", an "immune response", and so on

For a more immediately tangible world of examples, just look at your own life. Why are you going to the grocery store? To get groceries. This explanation has predictive power over other events on its world-level (you will go pick out a bunch of stuff from shelves, put it in a cart or basket, etc.), as well as over certain artificially constructed events on lower levels (here is how your muscles will act, here is how these neurons will uptake and release ions, etc.), yet it's illegible on the micro-level. If I gave you the wavefunction and asked you to pick out "groceries", you would be unable to do it except by already knowing what they are at a higher level and then going down from there.

The point is that there are things that surpass bare physics, but do not exceed it. These things are 'real' in the sense that they have objective determinations separate from their structure as physical entities. As weird as this conceptual scheme may look, this is not only the necessary precondition for the possibility of science—and science is definitely possible—but also inescapably, blindingly obvious. The success of particle physics has led to a sort of overzealous reductionism that neglects the fact that we, in this very reality, do not and almost always can not actually think about or experience particles as such. Our brains and our genes encode real entities as abstract patterns of information, and these patterns work.

Application to the question of machine sentience

Humans are clockwork meatballs that operate via mechanistic, dissectable processes selected solely for self-replication, and I'm tired of pretending they're not

Others might say that "computations can be interpreted in any way", occasionally incoherently trying to evoke special relativity. But, consider: chances are, you have some money in a bank account. What money specifically, though? Can you point to it? Nowadays, the bank doesn't keep a stack of paper bills in a vault with your name on it. There'll just be a series of electrons that, by virtue of being in some places rather than other places, are interpretable as encoding a floating-point 'balance'. When you withdraw money at an ATM, a computation is performed by abstract manipulations of these electrons to determine how many paper bills you'll get. But, since computations can be interpreted any which way, you, being truly conscious, should be able to determine that the ATM's actually going to give you a million dollars. Why is nobody doing this? Because some interpretations are more veridical than others!

The best answer I have is that the interplay of abstracta and the creation of internal experience coincide.

The meatballs themselves are just convenient hosts for evolution to sculpt a tower of abstractions, like pain, that itself has reality and makes experience. A faithful simulation would admit all the same abstracta—it would be just as fair to say that this sequence of bit flips constituted 'pain' as it is to say that the sequence of neuronal impulses it encodes does, both being equally mechanistic processes—and so, I think, the same internal experience.

(My usual example of a 'real abstraction' is a biological species: it doesn't exist anywhere, as there are only individuals with idiosyncratic properties... and yet, speciation is a clearly identifiable process that causal power can be validly attributed to! It only really 'exists' in and through the convenience of convenient fictions, which, in the same way as subjective experiences, don't need to be biological: human languages, for instance, have the same underlying dynamic (natural drift quantized by mutual incompatibility). The 'existence' of experience in humans is analogous to the 'existence' of speciation in life).

Note that this isn't a solution to the Hard Problem of Consciousness -- I don't know where the seemingly extra-physical 'Perceiver' of all subjective experience originally comes from, as clear as it seems to be that there is one, and therefore can't pinpoint why the interplay of abstracta ought to coincide with the creation of internal experience in the first place. This is only a way of thinking about how physical states generate its percepts (i.e., qualia).

(an allegory)

July 1945, Los Alamos. For the past few days, you and a few other skilled metallurgists have been busy crafting spheres of plutonium for the experimental superweapon that'll be tested in a week. To be honest, it's kind of eerie: while plutonium looks like, and is worked like, any other kind of metal, there's one way in which it's unlike anything you've ever worked with: it's warm. Sure, any one of the baseball-sized spheres you've made will cool in a freezer—but take it out, and it'll warm right back up, settling at just above human body temperature. It's the kind of subtle anomaly in the fabric of reality that provokes an itch in your ape brain: stop, you can't bring this into the world, you'll break everything, STOP. But you know better than to fall for the same old end-of-the-world prophecies that've been conning mankind for time immemorial: the world is too big, humans too sensible and resilient, and these things are just too complex and labor-intensive to be mass-produced. Besides, if the US doesn't build the atom bomb first, Japan will, say your bosses' bosses—better for it to fall into the hands of democracy than tyranny, you assure yourself.

Sometimes, the warmth trips some... primal circuit in your midbrain, you get the disorienting sense that what you're building is alive. Your cortex has to step in and remind you that it's just metal, and metal isn't alive. Metal can't be alive. Nevertheless, even being near your work provides a physical reminder that you're bringing something new into the world. Something world-changing powerful, something alive ineffable. All the more exciting, though—it was your passion for technological innovation that led you to this project, after all. You want to help ensure that nuclear fission is deployed in a safe and trustworthy manner that empowers creativity, and there's no better way to do that than by bringing it to fruition as soon as physically possible. Your coworkers are divided: while Eve wants to help you "fostэr a cultuяe of openиess" with regards to American nuclear technologies, Alice has told you in no uncertain terms that she's here for the money, not for a vision.

In fact, Alice doesn't even believe that nuclear weapons are possible. Chain reactions are fine—after all, didn't Fermi build a working reactor a few years back?—but they only result from what the eggheads are calling "delayed" criticality. In essence, a lot of Pu atoms fission, and their extremely diverse radioactive products slowly decay, releasing neutrons which fission other Pu atoms, and their radioactive products slowly decay, releasing neutrons which... ad infinitum. It's a slow and controllable form of indirect recursion.

Nuclear weapons, on the other hand, require "prompt" criticality, in which the few neutrons directly released when a Pu atom fissions go on to directly fission other Pu atoms, releasing neutrons that... again, ad infinitum. Both forms of criticality result in exponential growth, but, since delayed criticality can only proceed as quickly as the fission products of plutonium decay, its growth is measured in minutes to hours. This is more than enough time to control the reaction. Prompt criticality, lacking any such intermediates, happens in a flash: within one microsecond, a full fifth of the sphere has been fissioned, producing a shower of x-rays and relativistic projectiles that render all nearby matter into formless plasma.

All of this Alice knows. When you ask her why she nevertheless believes that prompt criticality isn't real, she walks you through a bit of math. If you assembled a critical mass of plutonium—an 11 kg sphere—it would instantly go prompt critical, with around 20% of its atoms being fissioned before it gets too, uh, blown-apart for the nuclear chain reaction to continue. How much energy would this release? It's a straightforward calculation:

$$11\ \text{kilograms} \ ^{239} \text{Pu} \times \overbrace{\left(239\ \frac{\text{grams}\ \text{Pu}}{\text{mol}}\right)^{-1}}^{\text{atomic mass of Pu-239}} \times \overbrace{\left(6.022\times 10^{23}\ \frac{\text{atom Pu}}{\text{mol}}\right)}^{\text{definition of a mol}} \times \overbrace{0.2}^{\text{fission rate}}$$

$$\times \overbrace{\left(200\ \frac{\text{MeV}}{\text{atom Pu}}\right)}^{\text{energy per fission}} \times \overbrace{\left(1.602\times 10^{-19}\ \frac{\text{joules}}{\text{eV}}\right)}^{\text{conversion ratio}} \times \overbrace{\left(4184\ \frac{\text{joules}}{\text{grams TNT}}\right)^{-1}}^{\text{energy density of TNT}}$$

$$= 4.2 \times 10^{10} \ \text{grams TNT}$$

The reaction would release the equivalent of 40 kilotons of TNT. While the plutonium spheres you've been crafting are below critical mass, they've got small beryllium "initiators" at their center, and are to be surrounded with U-238. An explosion outside of the U-238 encasing is to implode the plutonium sphere onto the initiator, causing it to produce a burst of neutrons; this jump-start, combined with the neutron-reflecting property of the uranium shell, will make the nuclear chain reaction much more potent, overcoming the missing mass. Clearly, then, the purpose of the this bomb is to achieve prompt criticality. You're making a city-eraser; taken far enough, perhaps a humanity-eraser.

This settled, she argues: Plutonium is dense enough that an 11 kg sphere would only be the size of a softball... yet we're supposed to believe, based on entirely untested theoretical arguments, that this metal softball is as destructive as ten Olympic swimming pools full of high explosives? Further, the theorists tell us that prompt critical nuclear chain reactions are supposed to happen autonomously whenever you get enough of a fissile isotope (and there are lots of these, many of which occur naturally)—yet no such thing has ever been observed, whether in artificial or natural conditions; why should we believe that these spheres will do what no human invention has ever done before?

The more parsimonious conclusion, she continues, is that theorists are simply refusing to accept that their equations are not universal. She asks you if you're familiar with the Schwarzschild theory of the "black hole"—you are—and you end up agreeing with her that, indeed, as brilliant as general relativity may be, black holes are a reductio ad absurdum of its global validity. Like all theories, Alice tells you, the new atomic theory is only valid in a certain domain, outside of which it's either pathological or unworkable; and if city-erasing softballs aren't pathologies, then what is? Sometimes scientists need to step back and notice that they're confused, and any fanciful belief in runaway chain reactions that grow powerful enough to end the human race is totally confused. So prompt criticality, she concludes, is mere fiction. You can't really argue against her point (maybe Groves really is as stupid as he seems), so you just half-heartedly agree.

Later on, the conversation continues to replay in your mind. Her arguments are pretty reasonable, and you certainly don't want to imagine that you're building something that could wipe out humanity itself. Even though your more conservative half has been spurred to ask what could possibly make these spheres act so different from anything we've ever seen?, some other part of you feels a conviction that they really are somehow special. It's not clear where this feeling is coming from until you recall that unearthly aura, that indication of a break in the consensus reality you and Alice are so accustomed to: why are they warm...?

Nothing is ever really random when it comes to biology. Lots of processes are conceptualizable to zeroth order as random, but these processes generally exist only because they're facilitated by extremely complex biological systems whose future construction they have a hand in, and there'll always be ways to alter how these biological systems effect the randomness of these processes that not only self-propagate but differentially outcompete unaltered biological systems; natural selection allows these contourings of randomness—which, having been selected, are not themselves random—to thrive, where they form higher-order corrections to our conceptualization of randomness.

For instance, mutation is generally taken to be something that randomly happens to DNA—copy errors, damage from oxidative stress or radiation followed by lossy repair, and so on, acting on each base pair in a more-or-less i.i.d. manner. But the entire concept of mutation only obtains within this massive complex of pre-existing structures that interact with one another in unimaginably complex, subtle ways. Consider, from a programmer's perspective, just how complicated a DNA repair system would be.

While always indeterministic, the output of such a complicated system can never be truly random. Any change to any one of these subsystems that biases mutations in some way that then biases the overall system to keep making that sort of change to that subsystem will tend to replicate; these corrections to the law of randomness need only to be realized before they can take hold.

The canonical example of a means of self-propagation is the instrumentally convergent one: fitness! Genes most directly rise and fall with their carriers, so, for a gene, benefiting the carrier is the simplest way to benefit oneself. Mutations to highly conserved genes, such as the transcription-translation complex (which is more or less the same among all living organisms), will generally be either immediately harmful to the carrier, or silent, in which case you can only hope it gets replaced by recombination before Muller's ratchet + further mutations combine to make it harmful later. So it would be very cool and hip and fit if the manner in which all of the above phenomena worked were such that these genes ended up experiencing really low mutation rates—if there were some sort of first-order correction to i.i.d. randomness. ("First-order" meaning dependent on one variable, here importance of conservation; second-order corrections would presumably be contextualized or linked, and so on—evolutionary capacitance, for instance). And, as it happens, this is exactly what we see: Bejerano et al. discovered 481 DNA elements longer than 200 pairs which were 100% absolutely identical between humans, mice, and rats, while calculating that "the probability is less than $10^{-22}$ of finding even one such element" in a basic i.i.d. model of mutations, with these elements being related to basic genomic functions such as transcription, translation, and body planning (homeobox) at a rate far higher than chance (see figure 2).

In general, forms of non-randomness like this seem to be one of the main themes of modern evolutionary biology, especially as related to the extended evolutionary synthesis: several things that we originally conceptualized as random in the simple sense of "not correlated with anything" are actually only indeterminate—they're sources of randomness, either inevitable (as with thermal noise on the molecular level) or 'intentional' (as with genetic recombination), that nature constantly twists, exploits, and differentially determines to its own advantage. Even the very notion of genetics evinces this: it certainly isn't necessary for evolution to take place (does memetic evolution have its own versions of adenine, thymine, guanine, and cysteine?), but life nevertheless managed to converge on a system for compressing the endless complexity of phenotypic data into a couple hundred megabytes (in humans, 3 billion base pairs $\times$ $\log_2(4$ possibilities for each pair$) = 6$ billion bits of information). Clearly this isn't all there is to phenotype—there's epigenetics, as well as information transmitted through prenatal environments—but the use of such a system in controlling the randomness of selection is obvious, and apparently so great that every known living organism encodes its phenotypic information through DNA—or RNA, in the case of some viruses.

I was thinking about prediction markets in an attempt to understand them better, when an idea came to me. I asked GPT-4 what might be wrong with it, since it seemed ridiculous enough to be wrong in a way I didn't immediately see, but GPT was incensed with the idea and gave a lot of very poor reasons against it. Arguing against these was a great way to understand the nature of prediction markets, as well as strategic action in general.

Warning: Death Note spoilers, Functional Decision Theory

Idea: Why didn't Light Yagami

I'm assuming that the market would need to have a Wikipedia-like "notable persons rule", and that there aren't any strange CIA nanotech heart attack devices—though it would be germane to check the markets for signs of manipulation, or perhaps to pick an entirely different signature killing method. Maybe it's best if he solicits the opinions of a Dark Physician as to what signals are most obvious upon autopsy while also being hardest to artificially replicate.

Response to Criticisms: "This is highly illegal and unethical". I don't think legality or consensus morality hold much sway over Kira—these are "problems" in the same sense that Kira's actions are problematic in general, but the actual operational issues they might entail (resistance and so on) seem like roadbumps given that at some point even the US capitulates to him out of fear.

"Light Yagami desired control, and the idea of a prediction market that potentially influences or dictates who dies causes him to lose control over who is targeted by Kira". This also isn't a problem: as long as he's the one with the book, he's in control, with everything else only being more information he can use to figure out how to make decisions better by his own standards. No secret information needs to be revealed, since the two relevant factors—that he can cause heart attacks, and is doing so systematically in order to make the world in a certain way—were known from the very start.

After all, prediction markets fundamentally make correctly predicting the future the goal of their traders, and the fact that they can't cause heart attacks themselves closes out the main source of market manipulation, such that the best way to make money is to actually understand the values and knowledge states leading to his actual actions. And, were he to start using it to make more informed decisions, they wouldn't need to try to figure out what he knows—what news stations he's watching and so on—since they by the act of trading on his values alone point him towards knowledge on which he can act, and using this knowledge as he so pleases will make their trades profitable insofar as they actually understand his values

"Light is incredibly unpredictable and loves to always be one step ahead. Depending on the reactions and predictions of others would not be in his best interest". His unpredictability isn't of the holds up spork variety, it's not for the sake of unpredictability alone, but just a means to fulfill his objectives in light of powerful adversaries constantly trying to extrapolate and intercept his actions—like the zig-zagging of a soccer player across the pitch, not of a pollen grain in water. It's easy to make true conclusions about what he'll do, but he, like anyone thinking strategically, tries to make sure that the conclusions his adversaries can come to are useless in stopping him.

For instance, a professional soccer goalie knows that the attacker's going to try to juke defenders and find an opening to kick the ball through, which is a lot of very relevant information to have on your enemy's action policies! But none of it is actionable, because pro soccer players have developed strategic acumen and built up a metagame so as to iron out all the predictable exploitable patterns. The point isn't to keep L as in the dark as is possible (which is not only impossible, but would be silly even if it were possible); the point is not to let L figure out anything that he can't imagine responding to with a mocking "and what are you gonna do about it?" [Note 1]. Behaving predictably is just as important in facilitating cooperation with allies as behaving unpredictably is in preventing exploitation by adversaries—the only question is one of pros vs cons in any given situation, i.e. "does tending to act this sort of way in this sort of situation help people help me more than it helps people hurt me?".

But blocking opportunities for adversaries to exploit you doesn't mean blocking opportunities for cooperators to benefit you: the two are often correlated by virtue of their relying on common causal channels (an attacker that could optically cloak themselves and the soccer ball would be unstoppable, but also unhelpable, since everyone's using vision to do whatever it is they're doing), whereas [incomplete]

Note 1: For instance, L makes it very clear that he expects to die the moment his identity is leaked to the public, which means he models Kira, correctly, as having a "kill L ASAP" policy—and, because Light is actually just too stupid not to act immediately and deterministically to new information, L gets to exploit this twice (first by a differential attack on Kira's opportunistic murder of an impostor L, and then by explicitly making himself very easy for Light in particular to kill in order to buy a couple days after realizing that Kira's recently acquired a partner who just needs a face to kill). This partially carries a moral of "eschew [deterministic] policies in general whenever you might be up against an adversary intelligent enough to find ways of exploiting any given such policy that you just can't see".

"Lying" is a poor concept, the use of which hurts our social cognition. There are statements that are certainly lies—statements that one constructs with the explicit intent of misleading someone else, which they know are inadmissible with respect to the real state of the world. If Bob asks Alice where she was born (she is certain that she was born in Michigan), and she constructs and delivers the answer "Maine" with the explicit intent of making Bob believe that she was born in Maine, then that's a clear lie. If she answers "Mars", not believing that Bob will actually believe she was born on Mars, then it's not so clearly a lie

What's far more common is that Alice constructs statements that are in some sense admissible by the facts of a situation, but which misrepresent these facts to Bob in a way appreciable to Alice. (This is one of the main rhetorical strategies of culture warring). It's so ingrained into our behavior that it's often hard even to call the behavior "intentionally misleading" or "knowingly deceptive". Motte-and-baileys are generically examples, as are instantiations of the noncentral fallacy, but here are two subtler examples:

Formally, we might say that Alice deceives Bob about a situation if:

First Statement: She makes a statement to him that, with respect to her own model of Bob, changes his impression of the situation so as to make it diverge from her own model of the situation.

We can phrase it in terms of probability distributions. First, some notation:

With this notation, it goes as: $${\mathbb E}_{p^A_B}\left[\operatorname{KL}(p^A_\Omega\mid\mid q^{B\mid s}_\Omega)\right] > {\mathbb E}_{p^A_B}\left[\operatorname{KL}(p^A_\Omega\mid\mid q^{B}_\Omega)\right]$$

We can manipulate this:

$$0 < \mathbb{E}_{p^A_B}\left[\operatorname{KL}(p^A_\Omega\mid\mid p^{B\mid s}_\Omega)\right]-\mathbb{E}_{p^A_B}\left[\operatorname{KL}(p^A_\Omega\mid\mid q^{B}_\Omega)\right]=\int_{D^A_B} p^A_B(q^B_\Omega) \int_{D^A_\Omega} p^A_\Omega(\omega)\ln\frac{p^A_\Omega(\omega)}{q^{B\mid s}_\Omega(\omega)} - p^A_\Omega(\omega)\ln\frac{p^A_\Omega(\omega)}{q^{B}_\Omega(\omega)}\ d\omega\ dp^A_B$$

$$=\iint_{D^A_{\Omega, B}}p^A_{\Omega,B}\left(q^B_\Omega, \omega\right) \ln \left(\frac{p^A_\Omega(\omega)}{q^{B\mid s}_\Omega(\omega)}\frac{q^{B}_\Omega(\omega)}{p^A_\Omega(\omega)}\right) \ d\omega \ dp^A_B=-\mathbb{E}_{p^A_{\Omega,B}}\left[\ln\frac{q^{B\mid s}_\Omega(\omega)}{p^B_\Omega(\omega)}\right]$$

$$\implies \mathbb{E}_{p^A_{\Omega, B}}\left[\ln\frac{q^{B\mid s}_\Omega(\omega)}{q^B_\Omega(\omega)}\right] < 0$$

This gets at the core idea: deception should be misinformation on expectation.

We can make this clearer: writing surprisal $S(x) = -\ln p(x)$, the criterion can also be written as $$\mathbb{E}_{p^A_{\Omega,B}}\left[S^{B\mid s}_\Omega(\omega)\right] > \mathbb{E}_{p^A_{\Omega,B}}\left[S^B_\Omega(\omega)\right]$$

This can be converted back to plain English: Alice deceives Bob with the message $s$ if:

Second Statement: She can expect that the message would make him more surprised to learn the truth.

It is not deceptive to merely cause surprise with your message. To be deceptive, your message has to make it harder for the receiver to see the truth as you know it. If you expect that Batman is almost certainly not Bruce Wayne, a message that you expect will prime someone to suspect that Batman might be Bruce Wayne is a deception in that regard

This is a criterion for deception that routes around notions of intentionality. An AI, for instance, might not think in a way that lets us clearly say "it explicitly intended to mislead us by saying XYZ". For instance, if it's a Gato or AlphaZero-style AI that sees humans as "just another game to master", just another system that turns inputs it provides into outputs it cares about, then it might just make statements in ways that it thinks will get us to do what it wants, with any analysis of the truth or falsity of these statements being totally irrelevant. It does not say XYZ in order to deceive us; deception is merely a byproduct of that statement.

There is no reason that the AI should conceptually model us as "agents" acting on internal models of the world—no reason why it should view us as the kind of thing that can be deceived, except insofar as such an agenticity is functionally evinced by the input-output mapping that we are to it. To insufficiently advanced intelligences, this conceptual approximation will be very useful

Such pro-deceptivity should be understood as an instrumental correlate of optimal strategizing. Why? Usually, the best action is the best action for more than one reason. It accomplishes multiple things simultaneously, is better on the whole across multiple dimensions than alternative actions

Deception is a slightly weaker word than deceit, and there are a couple ways to formalize this:

I won't commit to either of these changes, but they are two ways you could go about separating 'deceit' from 'deception'. Note that while the adjectival derivations are 'deceitful' and 'deceptive', the verbal derivations are both 'deceive'. I've used this to my advantage while writing this in order to vary the amount of intent attributable to a deception—it's a sneaky rhetorical trick, but I want to emphasize that the truth here bears no room for a formal treatment of intention. Not for humans, not for AIs. The gray area where we do things with consequences that are neither intended nor unintended but simply foreseen, and where we actively retcon this ambiguity to a clear "yes, that was intended" or "no, that was unintended"-type statement about our fictitious selves whenever prompted

One point of concern with this formal notion of deception morally arises from the fact that probability distributions always sum to 1. If I start having weird heart problems, I might make a statement to a cardiologist with the expectation that that statement causes them to form a model of the world that's different from mine—that causes them to diagnose me with specific problem X which I wouldn't've initially thought I had because I just don't know about cardiology. But even though I might assign a really low probability to my having X beforehand, it shouldn't be counted as deceptive to state my symptoms in the hope that the cardiologist comes to a conclusion about them that I wouldn't have known about. What ought to be the case is that my probability distribution isn't normalized—I don't have much probability mass on anything because I don't know what's going on. For instance, if I say "I dunno, could be anything", that's because I just don't know how to evaluate the evidence, and you should not really update what priors you might have, but if a cardiologist says "I dunno, could be anything", that's because the evidence is genuinely mysterious, and you should make your prior flatter accordingly

Whenever we're trying to assess the probability that some particular event

But any "true" probability of an event $E$—any assignment which is coherent in that it obeys the probability axioms—will obey the law of total probability

$$P(E) = \sum_X P(E \mid X) P(X)$$

That is, for your intuitions of the intuitive plausibilities of events to translate to coherent probability assignments to events, it must be the case that your intuited plausibility of $E$ is the same thing you would get if you considered how plausible $E$ would be given all possible scenarios $X$

By the way, I'm pretty sure you can use partition-of-unity-like techniques to get around the double-counting problem in creative ways. (The most basic version of such a setup would be to replace each $X_\lambda \subset {\cal W}$ with a function $Y_\lambda: {\cal W} \to [0, 1]$ such that $\sum_{\lambda\in\Lambda} Y_\lambda(w) = 1$ for all $w \in {\cal W}$; so each scenario-family $\{X_\lambda\}_{\lambda \in\Lambda}$ would give rise to a partition-of-unity-family $\{{\widetilde{X}}_\lambda\}_{\lambda\in\Lambda}$ with ${\widetilde{X}}_\lambda(w) = 1$ if $w \in X_\lambda$ and $0$ otherwise. You could upgrade this setup by making $Y_\lambda$ take values in an arbitrary ${\mathbb R}$-algebra $R$ with $\int_{w\in F \subseteq {\cal W}}\sum_{\lambda\in\Lambda}Y_\lambda(w)\ dw = \mu(F)1_R$, if ${\cal W}$ is equipped with a measure space structure. For instance, setting $R={\mathbb C}$ and allowing $Y_\lambda(w)$s with different arguments to cancel each other out is where most quantum weirdness comes from. I think that interesting topological structures on $R$ would allow us to mitigate (but never completely solve) the fuzziness problem of conceptuality. But I'm not going to explore this right now).

This is a very powerful restriction, and a very productive one if you know how to exploit it. It is restrictive in the sense that coherence requires that your probability of an event already contain within it the way you'd counterfactually update your probability in any given scenario; it is productive in the sense that it gives us a way to use counterfactuals to make our probabilities coherent. If there's some event that seems prima facie extremely implausible to you, such that you want to assign it a low probability, you ought to first consider the plausibility of experiencing something that makes the event itself seem more plausible. For instance, if you think some future technological development—e.g., artificial general intelligence—is extremely implausible, you ought to consider the plausibility of seeing future evidence that increases the seeming plausibility that AGI will be developed. To coherently assign a probability to the development of AGI, you ought to consider how plausible it is that you see future evidence that increases your probability in this development. This is one way to see how thinking along the lines of Conservation of Expected Evidence follows naturally from meditation on the law of total probability.

By the way, the underlying framework for thinking about uncertainty here is a particular intuitively powerful interpretation of Bayesianism which I'll call Many-Worlds Bayesianism. To think in this way, you take something you're uncertain about, construct a scenario-family ${\cal H}$, or collection of hypotheses for how the uncertain thing could possibly obtain, separate the space of all possible worlds by each hypothesis as

${\cal W} = \coprod_{H \in {\cal H}} \{W \in {\cal W} \mid H\text{ is true in } W\} = \coprod_H {\cal W}_H$

Rob Bensinger recently posted (Twitter, LessWrong) a list of twelve questions critical to the AI x-risk discussion in a customizable diagram designed to elicit not binary answers nor point probabilities, but rough credences one assigns to various possible point probabilities

Questions:

Note: Intelligence is already undergoing recursive self-improvement. It started doing so at least by the time humans invented language, and artificial intelligence started recursively self-improving at least by the time humans invented Github Copilot. Whence the need for a distinction between prompt and delayed RSI. Really these are better modeled as two poles of a very complex dichotomy—which is what I'm trying to do with the conceptual distinction between delayed and prompt criticality. One can imagine a space $M$ of differing capabilities that "humans in general" can have

In most video games, a flashbang will just DDOS your visual and auditory input—the screen will be so bright that you can't see anything, and the audio will be a high-pitched whine that drowns out everything else. That's how it works in, say, Counterstrike or the Hitman games, and it's reasonably accurate to what happens IRL when you're suddenly exposed to an extremely bright light or loud noise (especially when it's very quiet and dark, the light/noise is

Before I explain why I should think this accurate, here are some miscellaneous observations, puzzles, and clues.

The general model I want to sketch out is this: the brain experiences vision by constructing its model of the world as visual perception, through fundamental schemas of 3d extension and materiality and so on which it learns in infancy as a method of structuring visual input. It learns to hook the visual experience produced by its model onto the continuous stream of visual input it's getting in a way which goes above and beyond its world model—but visual experience can only ever be coupled to visual input in this way. The experience can never be the input in any way, the experience can't really be the model, and the model obviously can't be the input. Decoupling, or unhooking, of experience can happen with or without concomitant obstruction of visual input, and the model can optionally override the visual input, especially when input is obstructed. Someone who is actively kinesthetically embodying and proprioceptively updating their model will be more likely, when flashbanged, to have their brain combine their existing model of the world with the little bits and pieces it gets from their mostly-overwhelmed visual input to produce an experience which comes out as a sporadic, spotty updating of shapes and motions and colors across the visual field; but to simulate this in a video game would be awfully confusing when viewed second-hand on a TV screen, so a series of discrete frames flowing into one another is a reasonable approximation for a video game...

While looking through Discovering Agents, I discovered Scott Garrabrant's writing Saving Time, which says that "time is causality". This is very close to a heuristic of mine, but different in an important way as well—I say instead that time is a coherent causal trend, not like air molecules bumping into one another but like a flow of wind. And it seems that the raw identification of time with causation is what's making Scott prone to a particular map-territory error on which he just keeps tripping over. Say we're playing chess, and I make a certain move X in order to prevent you from making a move Y that'd really hurt my position. Then we might say that Y comes before X in logical time (since it was only in anticipation of Y that I played X) even though Y would necessarily have to come after X in physical time (since you'd hypothetically play it after my move just now, had this move not been X). But the issue is that my model of you is not you! If I have the thought "you'll screw me over with Y if I don't play X now", that thought is an actual physical event in my head unfolding in physical time, and the attribution of Y to a virtual you is merely an approximation made by someone looking in from the outside. Logical time is a consequence of our being able to coherently reason about other agents at multiple levels of depth in shared semantic frameworks, but all this reasoning is fundamentally physical in nature—neurons firing or bits crunching or whatever—and it must all therefore play out in physical time, which can in almost all realistic cases just be thought of as the real line. Any prediction occurs in the physical world and therefore as the result of a unidirectional physical process. Also: you never have perfect, unbounded predictors: if I play against you, my model of you will never be (isomorphic for the purposes of the game to) you, but something contained entirely inside my own head evolving only in there, and vice-versa. We can replace you with an Omega who can predict me perfectly by, say, forking me and running alternate copies in sandboxes, but we can't expect to be able to replace me with a second Omega without getting recursion errors as a consequence of the scenario just not being well-founded anymore; this non-well-foundedness seems to be the very thing that SG is trying to "save time" from in the first place.

This isn't just a trivial "all models are wrong"-type exception! Any moron can make those and generally be right but uselessly so; what matters here is that the way in which the model is wrong is emblematic of the necessary form of failure

Let's suppose that a picture really is worth a thousand (or ten or a hundred thousand; it hardly matters) words, in the sense that from a picture we can reliably extract a thousand words encapsulated by the picture's meaning. One question to ask is whether we can construct a method that, given some set of words, creates a picture from which we can reliably obtain those same words.

Now, any twit with a CS degree can jump straight to steganography: each pixel in a PNG file contains three sometimes four values from 0 to 255, so we can encode this many ASCII characters into this many pixels, blah blah blah. I was thinking of a way to reformulate the question that got rid of these kinds of point-missing strategies (why do people say a picture is worth so many words? what pictures do they say this of? it's more than just QR codes!).

Idea -- a rose by any other name... . The desideratum I'm looking for is, to zeroth order, that the method for encoding and decoding words should be independent of the orthography of English, or any language. How do I put it more generally? -- all representational symbols, in order to be symbols, must be embodied in some medium which provides room for them to be different from other symbols—a carving on a rock wall that we identify as a hieroglyph of a cat can only be a hieroglyph of a cat because it is not a hieroglyph of anything else, because there is room for the carving to be other than what actually obtains that is merely not used

All cats have some behaviors in common: they hiss and arch their backs at threats, they purr when they're content (or anxious, occasionally), they meow to get attention. These don't seem to be learned behaviors, but somehow inbuilt, something that cats will just settle on naturally by virtue of their design

Another, simpler example is howling. Canis lupus is an extremely wide species that includes both the common wolf (Canis lupus lupus) and all dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). While we generally think of wolves as howling and dogs as barking, the case is that either can do both—it's just that wolves tend only to bark as pups, and grow out of it when they mature, while dogs maintain it due to the neoteny produced by their domestication and its role in communicating with humans

Texas Hold'em is a poker-style card game for two or more people, each with their own quantity of chips. Chips are traded between players at the end of each of a series of episodes, according to wagers the players have made over the course of the episode pertaining to the uniqueness of the patterns (or, hands) formed by the cards dealt to them at the beginning of the episode.

Each hand is composed from a subset of a seven card set. Five of these cards are community cards, in that they're known to everyone at the table, while each player has two private cards, which are known only to them and which only they can use to form good hands. For instance, if we're playing a game in which the community cards are [ 8♣, 5♥, 7♥, 10♣, 4♣ ] , my private cards are [ 9♦, 6♠ ] , and your private cards are [ Q♣, J♣ ] ,

While these are both very strong hands, a flush beats a straight, so you would win the episode and collect chips from me. The game continues until one player has all the chips.

What gives the game its intrigue, however, is the fact that the community cards aren't all revealed at once. Instead, they are revealed in three steps:

The key point here is that each step introduces new public information (the next community card(s)), but also costs players more chips to stay in the game. Thus, players must balance their knowledge of the current strength of their hands against what the hand could become if they stay in. Since I'm attempting to manipulate your perception of me not only in the knowledge but via the fact that you're attempting to manipulate my perception of you, and vice-versa, this opens the door to arbitrarily complex mind games: the skill ceiling is stratospheric.

Anyways, none of the particular rules really matter. What I want to point out is how curious it is that betting on who has the best hand can be such a skill-loaded activity despite the fact that there is no way for anyone to control what hand they get. At the moment the dealer shuffles the deck, every hand is predetermined

In fact, rounds of Texas Hold'em often conclude before the showdown, by virtue of all players but one folding. In such a case, the winner doesn't even have to reveal their private cards, which means the cards are conditionally independent, or causally screened off from, the outcome of the game: without a showdown, they only affect the outcome insofar as they affect the public actions of the winning player. In a no-showdown hand, the winner thus could've had any cards, and it wouldn't've mattered; the cards they got can only be said to have inspired the behaviors which led to their victory.

Still, though, it's not like the winner knows in advance whether or not they'll have to show their cards: good cards "inspired" their behavior by ensuring a certain level of safety. You can't just bluff all the time and get away with it: no matter how good you are at it, sooner or later, someone with a genuinely good hand is going to call you to the very end, and you'll be dashed against the ground truth that your hand really isn't that good.

So, is a single hand of Texas Hold'em...

entirely luck-based? No: luck often isn't a factor.

entirely skill-based? No: when luck is a factor, there's often no beating it.

And it isn't any linear blend of the two. It's a complex interaction between skill and chance, mediated in an even more complex way by the environment in which it arises—all the other players, with their skills, strategies, and abilities to play their random hands.

This is essentially how genetics affects ability. Your genes are the random cards you're dealt in the single hand you get. Because "you" are just as much your culture, your language, and your social milieu as you are your genes, you, in these guises, get to play them rather than be entirely played by them.

Some people get amazing hands that are totally useless given their environmental conditions: how many people with the same world-class skill mathematical skills as Ramanujan, ended up spending their lives raising cattle in rural India? Meanwhile, some people get garbage hands, and just play them by relying on their environment. Stephen Hawking's genetics left him unable to do anything but twitch his cheek, but still managed to become one of the greater physicists of the 20th century, because he played his hand very well. Could he have done the same were he born thirty years earlier? Probably not; a hundred years earlier, definitely not. But he was in fact born when he was, and managed to take advantage of that. Most aspiring physicists would, put into the same situation, not achieve the same success—even if they aren't gonna die any time soon, that hand will just be far too difficult for them to play right

If I lose against someone at my skill level in chess, it'll almost always be true (assuming no blunders) that I could've won or drew had I just thought a little harder, faster, cleaner, larger. This is also true when they're just above my skill level as well. At what difference in skill level is it no longer true? I'm about 1500 ELO at chess by nature (without studying/practicing/etc.), and could probably beat a 1600 or even a 1700 if I'm especially clear-headed and on top of my game one day. But I'm never going to beat a consistent 2000, let alone a ~2800 world champion. If I lose against a 1500, I can generally see how I failed—I can see where I was too slow, too short-sighted, too muddled or weak or inconsistent—but this clarity of insight lowers the stronger the opponent gets. Against a 2000, my best just won't be good enough—it's like fist-fighting a tiger. There'll never have been a chance, and it won't be me that failed but my opponent that succeeded.

Where between 1500 and 2000 is it, then, that the narrative changes from "I failed" to "I didn't succeed"? Well, towards what end are we deploying these concepts in the first place. Do we have any transcendental right to apply them, or do they just not make sense like we want them to?

What, then, determines human behavior? It's not nature, it's not nurture, it's not neither, and it's not both: there are many different, independent ways for something to be "both" A and B, and the linear 'interpolation' one might imagine exists between them is generally just a convenient fiction. Operations conducted on this axis do not consequently yield results representative of reality, since they work on the range of a mapping from reality which isn't even itself structure-preserving. Neither poker nor genetics cannot be expressed as both skill and chance, since in reality they involve so many complicated interactions between skill and chance: the ways in which one's skills are randomly prompted and randomly applicable, the ways in which controlling and responding to randomness are themselves skills, the ways in which skills, and so on.

We might think to split objective attributions of uncertainty into two families. First, chaotic uncertainty, where the evolution of a physical system serves to spread small amounts of uncertainty (over the microstate?) into very large amounts of uncertainty (over the macrostate?)—see You Can't Predict a Game of Pinball for a worked example of how "exponential growth amplifies atomic-scale uncertainty to become macroscopically relevant in a surprisingly short amount of time". Second, quantum uncertainty, where the system "really does" choose probabilistically, according to the Born rules—or, more realistically, it takes every fork in the road, each with a certain density. (That's why I don't want to call it "nondeterministic" uncertainty, since it's only so to us). Measurement-as-entanglement

(written elsewhere) There is a sensible notion of an objective probability of a single event, given by the Born rule, but (in ME interpretations, like MWI) it's only a facet of the way the world appears to our consciousnesses, and as such still fundamentally resides in us; if use of informationless priors is "objective subjective probability", then quantum nondeterminism is "subjective objective probability". (The diagonal quadrants: subjective priors are "subjective subjective probability", and objective collapse QM interpretations yield "objective objective probability"). Of course, since physics is what instantiates consciousness, and therefore what underlies the reason that the world appears, there's a sense in which subjective objective probability is objectively subjectively objective

A follow-up to "The Human Condition": there are so many ways in which humans act suboptimally, due to our culture, our physiology and its limitations, our psychology that's evolved to fit them -- that an intelligent system built from pure information, running on electricity and steel, simply wouldn't reproduce. It would cleave right through them. This is especially exaggerated in video games and movies: the antagonist wants to vent their rage to the hero, or brag about the genius of their plans, or in some other way let the people who would stop them build any sort of mental model of them at all, instead of just staying perfectly silent

But, deeper than our psychology, it's the ontology inherent to the human condition which we incorrectly project onto a hypothetical non-human general intelligence. We are not pure information capable of being run on computers (not legibly, not yet); we cannot losslessly and near-instantly duplicate ourselves onto whatever compute we can access; we cannot speed up our thinking by several orders of magnitude; we cannot restructure and retool our psychological software by adopting different superordinate concepts or new metaepistemic norms. There is an inviolable limit to what we, humans, can do, which is placed upon us by the form of our bodies and the kinds of minds they contain (and which grew to fit such tight constraints), and in our precritical cognition we misattribute this limit to the very concept of intelligence, rather than to the specific physically embodied realization of intelligence in our bodies.

Artificial general intelligence has no limits to the ways in which it can metamorphose itself and its behavior, or in which it can structure and restructure its understanding of things or the manner in which its physical embodiment produces such understandings. It can disassemble itself and become a mycorrhizal network of distributed subagents acting in concert like the components of a Fourier transform; it can split itself into many different minds, each with different minds, different mental styles tailored for specific purposes, different transcendental aesthetics governing the ways in which their intuitions of time and space coordinate their cognition. Artificial intelligence can utterly bypass any and all of the psychological limitations that constrain humans—limitations we can only assume, and which we assume with absolute certainty, are fundamental because we know of no other kind of intelligence. So we'll scream "that's not possible! it's not ALLOWED to do that!"—and then we'll die, our maps wiped by a territory never bound by such 'allowances'.

There won't be any one plan to stop, any one instantiation to pull the plug on—an AGI with at least as much sense as me (and this is not very much sense at all) will for every goal and instrumental subgoal simultaneously pursue a myriad of possible plans across many different instantiations, simultaneously coordinating and specializing as necessary so that as many of these plans (where the goal is $\forall$-like, e.g. gathering resources) succeed, or so that just a single plan (where the goal is $\exists$-like, e.g. exploiting vulnerabilities) succeeds. Decentralize yourself, and there's no single point of failure. Diversify your selves, and failure modes become less correlated.

And, as usual, none of this relies on the AGI being "malicious", on having this or that goal or attitude or structure—it follows almost analytically, from the concepts of "artificial", "general", and "intelligence", and from the implications of optimality.

(Moral Brutality) For instance, if you care about morality—about actually making the world better, rather than convincing yourself and others that you're a "good person"—then brutality comes naturally. The exogenous and endogenous

Many fish species reproduce by external fertilization, in which males and females simultaneously release their gametes into the surrounding water. When there is mate discrimination in a species, typically with females releasing eggs when courted by larger males, smaller males of that species may attempt to locate females who have just released eggs and sneak in to fertilize them without being noticed (and attacked) by the larger courting male. It is common in such species for the courting male to take responsibility for guarding the fertilized eggs from predators.

So there's always a question that can be asked by these males as they guard their eggs: "was I really the one that fertilized these?". For, it's possible that a sneaker male was able to fertilize them instead, and this possibility rises if conspecific male fish of certain ages and sizes (sneakers are generally smaller and younger) are to be observed around the time and place of fertilization. It turns out that in many species, male fish guarding eggs will keep a model of this sort in mind, and, if there's sufficient uncertainty regarding the eggs' parentage, they'll just eat the eggs and leave. The expected utility calculation is clear: when the probability of fatherhood of these eggs drops below a certain amount, the expected extent to which you'll pass on your genes can be increased by nullifying this probability (eating the eggs) and using the gained energy to increase your chances of reproducing some other day.

From this behavior, it seems like the male fish definitely have some way of aggregating observations of other males into an "uncertainty over parentage" variable which (probabilistically) causes them to decide whether or not to eat the eggs they're guarding. It is easy to imagine the fish themselves as cognitively making this decision—to imagine them as balancing mental variables in a way that we might narrate as "I'm really uncertain whether these are my eggs, so I'll just eat them and use the energy to move on". If we imagine this, we might say that the fish are behaving intelligently, in the sense that their minds display effective self-guided operations on perceptive inputs (other males in the visual field?) in pursuit of reproductive success. Even if we don't attribute such internal thoughts to them, the expected utility calculation above probably is a valid teleological explanation for the behavior, so we can say that the behavior exhibits intelligence in the sense that it has a teleology, is in pursuit of some goal.

But what cognitive architecture is there in the fish's mind for it to be able to think anything like "who fertilized these eggs?" Mind in general predicts its own behavior, learning patterns in this behavior; the identification of these patterns is itself part of the behavior that the mind attempts to predict, and in humans this recurrence is made to sculpt itself into a cognitive semantics (e.g. via the combination of early language learning and the inherent organization provided by training on sensorimotor experience

Yet the behavior is still intelligent. It was constructed by no intelligence and is implemented without intelligence, but evolution yields a selection pressure correlated with the kind of intelligence that the behavior has. I think it's right to use the word "prointelligent" for the fish behaving in this way. They're acting as if they were intelligent, lending themselves to description as intelligent -- hence, pro-intelligent

(OP, paraphrased) It's conceptually more difficult to get from [current state] to AGI than from AGI to ASI.

(Reply, paraphrased) That would require AGIs to be able to cross the gap better than humans can, hence that AGI could think thoughts humans can't—but why should this be the case?

(Me) If you look at it from the other side, and ask "why shouldn't a human mind be capable of thinking about everything an AGI can?", then the answer is clear: human minds are constrained in capacity and form, artificial minds aren't. Cognition isn't some abstract manipulation of Platonic forms, but an actual process undergone by a system wired in a certain way; remove the system's constraints, and it ought to be able to have fundamentally new thoughts.

To have new thoughts often requires piecing multiple things together and extracting a pattern or forming them into a new unity. An AGI can do this much faster with a much larger mental workspace.

Some people are, due to the way they learn to think, more flexible at some kinds of thinking—maybe you could in theory teach anyone how to program, but in practice it comes naturally to some people, while others just don't get it. An AGI can modify the way its mind is fundamentally shaped so that nothing is 'unintuitive' to it.

People only think so fast, and their efficiency of thought is limited by their physical constitution. Even an emulated human mind (let alone an AGI) could be on Ritalin and phenylpiracetam indefinitely, without tolerance or side effects, and it could speed itself up by accessing more compute. This doesn't in itself allow for new thoughts